|

History of Romanians

Romania is situated in Central Europe,

in the northern part of the Balkan peninsula and its territory is

marked by the Carpathian Mountains, the Danube and the Black Sea.

With its temperate climate and varied natural environment, which

is favorable to life, the Romanian territory has been inhabited

since time immemorial. The research done by Romanian archaeologists

at Bugiulesti, Valcea Country, has led to the discovery of traces

of human presence dating back as early as the Lower Palaeolithic

(approximately two million years BC).

|

Cucuteni pottery

|

These vestiges are

among the oldest in Europe, revealing a period when "man," a

humanoid in fact, went physically and spiritually through the

stages of his coming out of the animal status. A denser human

population, ("the Neanderthal man") can be proved to have lived

about 100,000 years ago; a relatively stable population can

only be found beginning with the Neolithic (6-5,000 years BC). |

| At the time, the

population on the territory of present-day Romania created a

remarkable culture, whose proof is the polychrome pottery of

the "Cucuteni" culture (comparable to the pottery

of other important European cultures of the time in the Eastern

Mediterranean and the Middle East) and the statuettes of the

"Hamangia" culture (the Thinker of Hamangia is known

today to the whole world). |

The Thinkers of Hamangia

(Neolithic statuette)

|

At the turn of the second millennium,

when the Palaeolithic age made way for the Bronze age, the Thracian

tribes of Indo-European origin settled alongside the population

that already lived in the Carpathian-Balkan region. From the time

of the Thracians on, the uninterrupted phenomenon of the Romanian

peoples birth can be traced. In the former half of the first millennium

BC, in the Carpathian-Danube-Pontic area - which was the northern

part of the large surface inhabited by the Thracian tribes - a northern

Thracian group became individualized: it was made up of a mosaic

of Getae and Dacian tribes. Strabo, a famous geographer and historian

in the age of emperor Augustus, informs that "the Dacians

have the same language as the Getae".

|

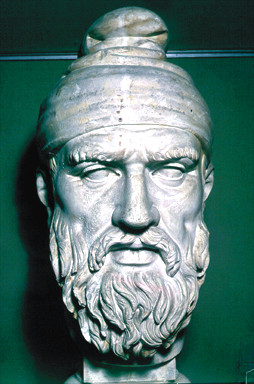

A Geto-Dacian nobleman

(tarabostes)

wearing the traditional pileus on his head

|

Basically, it was

the same people, the only difference between the Dacians and

the Getae being the area they inhabited: the Dacians - mostly

in the mountains and the plateau of Transylvania; the Getae

- in the Danube Plains. In the Antiquity, the Greeks, who first

got to encounter the Getae - used this name for the whole population

north of the Danube, while the Romans, who first got to encounter

the Dacians-extended this name to cover all the other tribes

on the present-day territory of Romania; after the conquest

of this territory, the Romans created here the Dacia province.

This is why the whole territory of present-day Romania is called

Dacia in all ancient Latin and Early Middle Ages sources. |

The contact of the Geto-Dacians with

the Greek world was made easy by the Greek colonies created on the

present-day Romanian Black Sea shore: Istros (Histria), founded

in the 7th century BC, Callatis (today: Mangalia) and Tomi (today:

Constanta); the latter two were founded a century later. In the

recorded history, the population north of the Danube (the Getae)

was first mentioned by Herodotus, "the father of history" (the 4th

century BC). He told the story of the campaign of Persian king Darius

I against the Scythians in the northern Pontic steppes (513 BC).

He wrote that the Getae were "the most valiant and just of the Thracians".

They had been the only ones to resist the Persian king on the way

from the Bosporus to the Danube.

|

The Dacian stronghold

of Sarmisegetuza

|

Burebista

(82 - around 44 BC), who succeeded to unite the Geto-Dacian

tribes for the first time, founded a powerful kingdom that stretched,

when the Dacian sovereign offered to support Pompey against

Caesar (48 BC), from the Beskids (north), the Middle Danube

(west), the Tyras river (the Dniester), and the Black Sea shore

(east) to the Balkan Mountains (south). |

In the 1st century BC, as the Roman

empire was expanding and Roman provinces were being created in Pannonia,

Dalmatia, Moesia and Thracia, the Danube became, along 1,500 Km.,

the border between the Roman Empire and the Dacian world. In Dobrudja,

which was under Roman rule for seven centuries beginning with the

reign of Augustus, poet Publius Ovidius Naso spent the last years

of his life, "among Greeks and Getae," as he was exiled there, to

Tomi (8-17, AD) by order of the same Caesar.

| Dacia was at the

peak of its power under King Decebal (87-106 AD). After

a first confrontation during the reign of Domitian (87-89),

two extremely tough wars were necessary (101-102 and 105-106)

to the Roman empire, at the peak of its power under Emperor

Trajan (98-117) to defeat Decebal and turn most of his kingdom

into the Roman province called Dacia. |

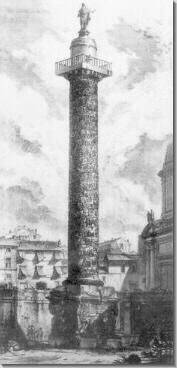

King Decebal

|

Emperor Trajan

|

|

Trajan's Column in Rome

-

the birth certificate of the Romanian people

|

Trajans

Column erected in Rome and the Triumphal Monument at Adamclisi

(Dobrudja) tell the story of this military effort, which was

followed by a systematic and massive colonization of the new

territories that were integrated into the empire.

|

| The Dacians, although

they had suffered heavy casuals, remained, even after the new

rule was established, the main ethnic element in Dacia; the

province was subjected to a complex Romanization process, its

basic element being the staged but definitive adoption of the

Latin language. |

The Roman monument of

Adam Clisi (second century AD)

|

The Romanians are today the only descendants

of the Eastern Roman stock; the Romanian language is one of the

major heirs of the Latin language, together with French, Italian,

Spanish; Romania is an oasis of Latinity in this part of Europe.

|

The Roman mosaic of Tomis

(Constanta)

|

The natives, be they

of Roman or Daco-Roman descent, continued their uninterrupted

existence as farmers and shepherds even after the withdrawal,

under emperor Aurelian (270-275) of the Roman army and administration,

which were moved south of the Danube. But the ancestors of the

Romanians remained for several centuries in the political, economic,

religious and cultural sphere of influence of the Roman Empire;

after the empire split in 395 AD, they stayed in the sphere

of the Byzantine Empire. They lived mostly in the old Roman

hearts that had now decayed and survived in difficult circumstances

under successive waves of migratory tribes. |

At the time when the Daco-Roman ethno-cultural

symbiosis was achieved and finalized in the 6-7th centuries by the

formation of the Romanian people, in the 2-4th centuries, the Daco-Romans

adopted Christianity in a Latin garb.

Therefore, in the 6-7th centuries,

when the formation process of the Romanian people was done, this

nation emerged in history as a Christian one. This is why, unlike

the neighboring nations, which have established dates of Christianization

(the Bulgarians - 865, the Serbs - 874, the Poles-966, the eastern

Slavs - 988, the Hungarians - the year 1000), the Romanians do not

have a fixed date of Christianization, as they were the first Christian

nation in the region.

In the 4-13th centuries the Romanian

people had to face the waves of migrating peoples - the Getae, the

Huns, the Gepidae, the Avars, the Slavs, the Petchenegs, the Cumanians,

the Tartars - who crossed the Romanian territory.

The migratory tribes controlled this

space from the military and political points of view, delaying the

economic and social development of the natives and the formation

of local statehood entities.

The Slavs, who massively settled since

the 7th century south of the Danube, split the compact mass of Romanians

in the Carpathian-Danubian area: the ones to the north (the Daco-Romanians)

were separated from the ones to the south, who were moved towards

the west and Southeast of the Balkan Peninsula (Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians

and Istro-Romanians). The Slavs that settled north of the Danube

were assimilated little by little by the Romanian people and their

language left traces in the vocabulary and phonetics of the Romanian

language. To the Romanian language, the Slavic language (similarly

to the Germanic idiom of the Franks with the French people) was

the so-called super-imposed layer. The Romanians belonged to the

Orthodox religion so they adopted the Old Church Slavic as a cult

language, and, beginning with the 14-16th centuries, as a chancery

and culture language. The Slavic language was never a living language,

spoken by the people, on the territory of Romania; it played for

Romanians, at a certain time during the Middle Ages, the same role

that Latin played in the West; in the early modern age it was replaced

for ever, in church, chancery and culture included, by the Romanian

language.

Owing to their position, the Romanians

south of the Danube were the first to be mentioned in historical

sources (the 10th century), under the name of vlahi or

blahi (Wallachians); this name shows they were speakers of a

Romance language and that the non-Roman peoples around them recognised

this fact.

After the year 602, the Slavs massively

settled south of the Danube and they established a powerful Bulgarian

czardom in the 9th century; this, cut the tie between the Romanian

world north of the Danube and the one south of the Danube. As they

were subjected to all sorts of pressures and isolated from the powerful

Romanian trunk north of the Danube, the number of Romanians south

of the Danube continuously decreased, while their brothers north

of the Danube, although living in extremely difficult circumstances,

continued their historical evolution as a separate nation, the farthest

one to the east among the descendants of Imperial Rome.

In fact the Romanians are the only

ones who, through their very name - roman - (coming from the Latin

word "Roman") - have preserved to this day in this part of Europe

the seal of the ancestors, of their descent, that they have always

been aware of. This will show later in the name of the nation state

- Romania.

Wallachia, Moldavia, Transylvania

Beginning with the 10th century, the

Byzantine, Slav and Hungarian sources, and later on the western

sources mention the existence of statehood entities of the Romanian

population - kniezates and voivodates - first in Transylvania and

Dobrudja, then in the 12-13th centuries, also in the lands east

and south of the Carpathians. A specific trait of the Romanians

history from the Middle Ages until the modern times is that they

lived in three Principalities that were neighbors, but autonomous

- Wallachia, Moldavia and Transylvania.

This phenomenon - which is by no means

unique in Mediaeval Europe - is extremely complex. The underlying

causes pertain to the essence of the feudal society, but there are

also specific factors. Among the latter, we wish to mention the

existence of powerful neighboring empires, which opposed the unification

of the Romanian state entities and even occupied - for shorter or

longer periods of time - Romanian territories. For instance, to

the west the Romanians had to face the policy of conquests conducted

by the Hungarian kingdom. In 895, the Hungarian tribes, who came

from the Volga lands, led by Arpad, settled in Pannonia. They were

stopped in their progress towards the west by emperor Otto I (995)

so the Hungarians settled down and turned their eyes to the south-east

and east. There they encountered the Romanians.

A Hungarian chronicle describes the

meeting between the messengers sent by Arpad, the Hungarian king,

and voivode Menumorut of the Biharea city in western Transylvania.

The Hungarian ambassadors demanded that the territory be handed

over to them. The chronicle has preserved for us the dignified answer

given by Menumorut: "Tell Arpad, the Duke of Hungary, your ruler.

Verily we owe him, as a friend to a friend, to give him all that

is necessary because he is a foreigner and a stranger and lacks

many. But the land that he has demanded from our good will we shall

never give to him, as long as we are alive".

|

The Church of Densus

|

Despite the resistance

of the Romanian kniezates and voivodates, the Hungarians succeeded

in the 10-13th centuries to occupy Transylvania and make it

part of the Hungarian kingdom (until the beginning of the 16th

century as an autonomous voivodate.) In order to consolidate

their power in Transylvania, where the Romanians continued to

be, over the centuries, the great majority ethnic element, as

well as to defend the southern and eastern borders of the voivodate,

the Hungarian crown resorted to the colonization of Szecklers

and Germans (Saxons) in the 12-13th centuries in the frontier

areas. |

| In the 14th century,

with the decline of the neighboring imperial powers (the Poles,

the Hungarians, the Tartars), south and east of the Carpathian

Mountains range the autonomous feudal states were formed: Wallachia,

under Basarab I (around 1310) and Moldavia, under

Bogdan I (around 1359). The Polish and Hungarian kingdoms

attempted in the 14-15th centuries to annex or subordinate the

two principalities, but they did not succeed. |

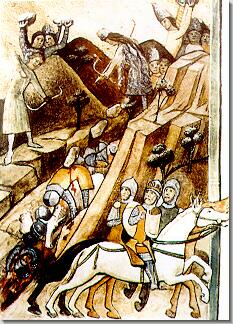

Scene from the Painted

Chronicle of Vienna showing

the victory of the Romanians at Posada (1330)

against the army of the Hungarian King

|

In the second half of the 14th century

a new threat against the Romanian lands emerged: the Ottoman Empire.

After first setting foot on European soil in 1354, the Ottoman Turks

began their rapid expansion on the continent, so the green banner

of the Islam already flew south of the Danube in 1396.

|

Mircea the Old,

Voivode of Wallachia (1386-1418)

|

Vlad the Impeller,

Voivode of Wallachia

(Dracula of the Mediaeval legends, 1456-1462)

|

Stephen the Great and

Holy,

Voivode of Moldavia (1457-1504)

|

Alone or in alliance

with the neighboring Christian countries, more often in alliance

with the neighboring voivodes of the other two Romanian principalities,

the voivodes of Wallachia Mircea the Old (1386-1418)

and Vlad the Impeller (Dracula of the Mediaeval legends,

1456-1462), with Stephen the Great and Holy (1457-1504),

the voivode of Moldavia and Iancu of Hunedoara, the

voivode of Transylvania (1441-1456) fought heavy defence battles

against the Ottoman Turks, delaying their expansion to Central

Europe. |

The whole Balkan Peninsula became

a Turkish-ruled territory, Constantinople was captured by Mohammed

II (1453), Suleiman the Magnificent captured the city of Belgrade

(1521), and the Hungarian kingdom disappeared following the battle

of Mohacs (1526). Therefore, Wallachia and Moldavia were surrounded

and they had to recognize for over three centuries the suzerainty

of the Ottoman Empire. After Buda was captured and Hungary became

a pashalik, Transylvania became a selfruling principality

(1541) and it, too, recognized the suzerainty of the Ottoman Empire,

as the other two Romanian lands.

| Unlike all the other

peoples of south-east Europe, unlike the Hungarians and the

Poles, the Romanians were the only ones who maintained their

state entity during the Middle Ages, along with their own political,

military and administrative structures. The tribute paid to

the sultan was the guarantee for the preservation of domestic

autonomy, but also for the protection against more powerful

enemies. |

City of Soroca on the

Dnister river bank

|

|

The Curtea de Arges Monastery,

founded by Neagoe Basarab

(1512-1521), Prince of Wallachia

|

Wallachia and Moldavia,

owing to their autonomy status, continued after the fall of

the Byzantine Empire to foster their Byzantine cultural traditions,

taking at the same time upon themselves to protect the Eastern

Orthodox religion; on their territory, scholars from all over

the Balkan Peninsula, chased away by the intolerant Islam, were

able to continue their work without any obstacles; they prepared

the cultural revival of their nations. |

| The end of the 16th

century was dominated by the personality of Michael the

Brave. He became voivode of Wallachia in 1593, joined the

Christian League - an anti-Ottoman coalition initiated by the

Papacy and the Holy Roman Empire and he succeeded, following

heavy battles (Calugareni, Giurgiu) to actually regain the independence

of his country. In 1599-1600 he united for the first time in

history all the territories inhabited by Romanians, proclaiming

himself "prince of Wallachia, Transylvania and the whole of

Moldavia." The domestic situation was very complex, the neighboring

great-powers - the Ottoman Empire, Poland, the Hapsburg Empire

- were hostile and joined forces to overthrow him; so this union

was short-lived as Michael the Brave was assassinated in 1601. |

Michael the Brave (1593-1601),

prince of Wallachia,

the first to unite the Romanian feudal states

|

|

Michael the Brave entering

Alba Iulia on November 1, 1599

|

The union achieved

by the valiant voivode became, however, a symbol to the posterity.

In the 17th century, in various forms and with evanescent success,

other princes attempted to restart the ambitious political program

of Michael the Brave, by trying to form a united anti-Ottoman

front, made-up of the three principalities and to restore the

unity of ancient Dacia.

Michael the Brave (1593-1601)

who first united the three Romanian lands.

|

The end of the 17th century and the

beginning of the 18th century brought about changes in the politics

of Central and Eastern Europe. The Ottoman Empire failed to capture

Vienna in 1683 and following that, the Hapsburg Empire began its

expansion to the south-east of Europe. The Austrian-Turkish peace

treaty of Karlowitz (1699) sanctioned the annexation of Transylvania

and its organization as an autonomous principality to Hapsburg Austria

(since 1765 great principality), ruled by a governor. Poland was

divided and Russia, by successive conquests, reached under Peter

the Great (1696-1725) the Dniester river, thus becoming Moldavias

eastern neighbor.

The ambitious dream of the czars to

dominate the Bosporus strait and Constantinople placed the Romanian

Principalities in the way of Russian expansionism. The Ottoman Empire,

in an attempt to defend its old position, introduced in Moldavia

(1711) and Wallachia (1716) the "Phanariot regime,"

(until 1821), under which the Sublime Porte appointed in the two

principalities Greek voivodes recruited from the Phanar district

of Istanbul and considered faithful to the Turks. That was a time

when the Ottoman political control and economic exploitation increased

and corruption spread; but some social reforms were also introduced

- such as the abolition of serfdom - as well as administrative and

modernizing reforms, modeled on the European ones in the age of

the Enlightenment. The domestic autonomy, although limited, was

basically preserved and the two principalities continued to be distinct

entities from the Ottoman Empire; this situation was recognized

in several international treaties (for instance that of Kuchuk-Kainargi,

1774). Lying at the borders of three great empires and wanted

by all three of them, Wallachia and Moldavia became for over 150

years not only territories of contention but also a battlefield

on which the armies of the empires fought each other.

Many wars were fought by Austria and

Russia against the Ottoman Empire (1710-1711, 1716-1718, 1735-1739,

1768-1774, 1787-1792, 1806-1812, 1828-1829, 1853-1856): those battles

took place on Romanian soil, always

accompanied by a foreign military occupation, which was often maintained

long after the war proper was over, so the Romanian lands endured

not only through devastation and irrecoverable losses but also through

population displacements and painful territory amputations. So,

Austria temporarily annexed Oltenia (1718-1793) and Northern Moldavia

that they called Bukovina (1775-1918). Following the Russian-Turkish

war of 1806-1812, Russia annexed the eastern part of Moldavia, the

land between the Prut and Dniester rivers, later called Bessarabia

(1812-1918).

National Revival

In the 18th and early 19th centuries

huge economic and social changes took place, the feudal structures

were deeply eroded, the first capitalist enterprises emerged and

at the same time Romanian goods were attracted step by step into

the European circuit. The national idea, as everywhere else in Europe,

was becoming the soaring dream of intellectuals and the underlying

element in the plans for the future made by the politicians.

| The union of part

of the clergy in Transylvania with the Catholic Church (the

Greek- Catholics), achieved by the House of Hapsburg in 1699-1701,

played an important part in the emancipation of Transylvanian

Romanians. Their fight for equal rights with the other ethnic

groups (although the Romanians accounted for over 60% of the

principates population, they were still considered "tolerated"

in their own country) was begun by Bishop Inocentiu Micu-Klein

and continued by the intellectuals grouped in the "Transylvanian

School" movement: Gheorghe Sincai, Petru Maior,

Samuil Micu, Ion Budai-Deleanu, a.o. |

Greek-Catholic bishop

Inocentiu Micu-Klein (1692-1768), promoter of the national

struggle

of the Romanians in Transylvania

|

These scholars proved the Latinity

of the Romanian language and people and, even more, the fact that

they had uninterruptedly been the autochthonous population here.

By virtue of this ancients, they demanded equal rights with the

other "nations" in Transylvania - Hungarians, Szecklers and Saxons.

The claims of the Romanians in Transylvania were submitted to the

Court of Vienna in the long petition called Supplex Libellus

Valachorum (1791), which did not receive any answer.

|

Tudor Vladimirescu,

the leader of the 1821 Romanian revolution

|

The quest for renewal

in Wallachia was expressed in the revolution led by Tudor

Vladimirescu (1821), which broke out at the same time with

the Greeks movement for liberation.

|

Although the Ottoman and Czarist troops

occupied the Danube principalities that same year, the sacrifices

made by the Romanians brought about the abolition of the Phanariot

regime and native voivodes were again appointed on the thrones of

Moldavia and Wallachia. The peace treaty of 1829 signed at Adrianople

(today Edirne) ended the Russian-Turkish conflict of 1828-1829,

which had broken out in the final stage of the war for national

liberation fought by the Greeks; this treaty greatly weakened the

Ottoman suzerainty, but it increased Russias "protectorate." Now

that trade was freed, Romanian cereals began to penetrate European

markets. Under Pavel Kiseleff, the commander of the Russian troops

that occupied the two Romanian principalities (1828-1834), quasi-identical

Organic Regulations were introduced in Wallachia (1831) and Moldavia

(1832); until 1859 these Regulations served as fundamental laws

(constitutions) and they contributed to the modernisation and homogenisation

of the social, economic, administrative and political structures

that had started in the preceding decades. Therefore, in the first

half of the 19th century, the Romanian principalities began to distance

themselves from the Oriental Ottoman world and tune into the spiritual

space of Western Europe. Ideas, currents, attitudes from the West

were more than welcome in the Romanian world, which was undergoing

an irreversible process of modernization. Now the awareness that

all Romanians belong to the same nation was generalized and the

union into one single independent state became the ideal of all

Romanians.

Union and Independence

The winds of 1848 also blew over the

Romanian principalities.

| They brought to the

centre-stage of politics several brilliant intellectuals such

as Ion Heliade Radulescu, Nicolae Balcescu, Mihail Kogalniceanu,

Simion Barnutiu, Avram Iancu and others. |

Nicolae Balcescu, one

of the 1848 revolution leaders

|

In Moldavia the unrest was quickly

cracked down on, but in Wallachia the revolutionaries actually governed

the country in June-September 1848.

|

Avram Iancu,

leader of the 1848 Romanian revolution in Transylvania

|

In Transylvania the

revolution was prolonged until as late as 1849. There, the Hungarian

leaders refused to take into account the claims of the Romanians

and they resolved to annex Transylvania to Hungary; this led

to a split of the revolutionary forces between the Hungarians

and the Romanians. The Hungarian government of Kossuth Lajos

attempted to crack down on the fight of the Romanians, but he

encountered the resolute armed resistance of the Romanians in

the Apuseni Mountains, under the leadership of Avram Iancu. |

Although the brutal intervention of

the Ottoman, Czarist and Hapsburg armies was successful in 1848-1849,

the renewal tide favoring democratic ideas spread everywhere in

the next decade.

Russia was defeated in the Crimean

War (1853-1856) and this called into question again the fragile

European balance. Owing to their strategic position at the mouth

of the Danube, as this waterway was becoming increasingly important

to European communications, the status of the Danube principalities

became a European issue at the peace Congress in Paris (February-March

1856). Wallachia and Moldavia were still under Ottoman suzerainty,

but now they were placed under the collective guarantee of the seven

powers that signed the Paris peace treaty; these powers decided

then that local assemblies be convened to decide on the future organization

of the two principalities. The Treaty of Paris also stipulated:

the retrocession to Moldavia of Southern Bessarabia, which had been

annexed in 1812 by Russia (the Cahul, Bolgrad and Ismail counties);

freedom of sailing on the Danube; the establishment of the European

Commission of the Danube; the neutral status of the Black Sea.

In 1857 the "Ad-hoc assemblies" convened

in Bucharest and Iasi under the provisions of the Paris Peace Congress

of 1856; all social categories participated and these assemblies

unanimously decided to unite the two principalities into one single

state. French emperor Napoleon III supported this, the Ottoman Empire

and Austria were against, so a new conference of the seven protector

powers was called in Paris (May-August 1858); there, only a few

of the Romanians claims were approved.

| But the Romanians

elected on January 5/17, 1859 in Moldavia and on January 24/February

5, 1859 in Wallachia Colonel Alexandru Ioan Cuza as

their unique prince, achieving de facto the union of the two

principalities.

The Romanian nation state took

on January 24/February 5, 1862 the name of ROMANIA and settled

its capital in Bucharest.

|

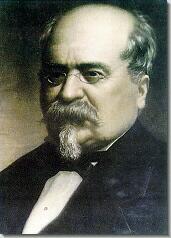

Alexandru Ioan Cuza

(1859-1866),

Voivove of the United Principalities

|

|

Mihail Kogalniceanu (1817-1890),

father of the program to make Romania a modern country

|

Assisted by Mihail

Kogalniceanu, his closest adviser, Alexandru Ioan Cuza initiated

a reform program, which contributed to the modernization of

the Romanian society and state structures: the law to secularise

monastery assets (1863), the land reform, providing for the

liberation of the peasants from the burden of feudal duties

and the granting of land to them (1864), the Penal Code law,

the Civilian Code law (1864), the education law, under which

primary school became tuition free and compulsory (1864), the

establishment of universities in Iasi (1860) and Bucharest (1864),

a.o. |

| After the abdication

of Alexandru Ioan Cuza (1866), Carol of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen,

a relative of the royal family of Prussia, who was supported

by Napoleon III and Bismark, was proclaimed on May 10, 1866,

following a plebiscite, ruling prince of Romania, with the name

of Carol I. |

Carol I, first King

of Romania

|

The new Constitution (inspired from

the Belgian one of 1831), which was promulgated in 1866 and was

in use until 1923, proclaimed Romania a constitutional monarchy.

In the next decade the struggle of the Romanians to achieve full

state independence was part of the movements that took place with

other peoples in the south-east of Europe - Serbs, Hungarians, Montenegrins,

Bulgarians, Albanians - to cut off their last ties to the Ottoman

Empire. Within a favorable international framework - in 1875 the

Oriental crisis broke out again and the Russo-Turkish war started

in April 1877 - Romania declared its full state independence on

May 9/21, 1877. The government led by Ion C. Bratianu, in

which Mihail Kogalniceanu served as Foreign Minister, decided, upon

the Russian request for assistance, to join the Russian forces that

were operative in Bulgaria.

|

Attack of Grivita stronghold

Engraving of the Independence War period (1877-1878)

|

A Romanian army,

under the personal command of Prince Carol I, crossed the Danube

and participated in the siege of Pleven; the result was the

surrender of the Ottoman army led by Osman Pasha (December 10,

1877). |

The independence of Romania, similarly

to that Serbia and Montenegro, as well as the union of Dobrudja

with Romania were recognized in the Russian-Turkish peace treaty

of San Stefano (March 3, 1878). Upon the insistence of the great

powers, an international peace Congress was held in Berlin (June-July

1878), which acknowledged and maintained the status that Romania

had proclaimed by herself more than a year before; it also re-established,

after a long period of Ottoman rule, Romanias rights over Dobrudja,

which was re-united to Romania. But at the same time Russia violated

the convention signed on April 4, 1877 and forced Romania to cede

the Cahul, Bolgrad and Ismail counties of Southern Bessarabia.

On March 14/26, 1881, Romania proclaimed

itself a kingdom and Carol I of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen was crowned

King of Romania.

After gaining its independence, the

Romania state was the place to which the hopeful eyes of all Romanians

who lived on the lands still under foreign occupation turned. The

Romanians in Bukovina and in Bessarabia were facing a systematic

policy of assimilation into the German and Russian worlds, respectively.

Immigration of foreign peoples was directed to their territory.

The Romanian enclaves in the Balkan Peninsula had increasing difficulties

in opposing the denationalization tendencies. At the turn of the

20th century, the Romanians were a people with over 12 million inhabitants,

of whom almost half lived under foreign occupation.

At the same time in Transylvania,

the Romanians suffered the serious consequences of the accord by

which the Hungarian state was re-established more than three centuries

after its collapse and the dual Austria-Hungary state was created

(1867). Transylvania lost the autonomous status it had under Austrian

rule and it was incorporated into Hungary. The legislation passed

by the government in Budapest, which proclaimed the existence of

only one nationality in Hungary - the Magyar one - sought to destroy

from the ethno-cultural point of view the other populations, by

forcing them to become Hungarian. This subjected the Romanian population,

along with other ethnic groups, to heavy ordeals. At that time the

National Romanian Party in Transylvania played an important role

in asserting the Romanian national identity; the party was reorganized

in 1881 and it became the standard bearer in the struggle to achieve

recognition of equal rights of the Romanian nation and it the resistance

against the denationalization projects.

| In 1892 the national

struggle of the Romanians reached a climax through the Memorandum

Movement. The memorandum was drafted by the leaders of the Romanians

in Transylvania, Ion Ratiu, Gheorghe Pop of Basesti, Eugen

Brote, Vasile Lucaciu, a.o. and it was sent to Vienna to

be submitted to emperor Franz Joseph I; it advised the European

public opinion of the Romanians claims and of the intolerance

shown by the government in Budapest regarding the national issue. |

The Group of memorandum

champions,

members of the Romanian National Party of Transylvania, sentenced

to hard years of prison by the

Hungarian courts of law in 1894

|

The 1878-1914 period was one of stability

and progress for Romania. Politics got polarized around two huge

parties - the conservative one (Lascar Catargiu, P.P. Carp, Gh.

Grigore Cantacuzino, Titu Maiorescu, a.o.) and the liberal one

(Ion C. Bratianu, Dimitrie A. Sturdza, Ion I.C. Bratianu,

a.o.). They alternatively came to power and this became the characteristic

trait of the epochs politics.

The expansionist policy of Russia

determined Romania to sign in 1883 a secret alliance treaty with

Austria-Hungary, Germany and Italy; the treaty was renewed periodically

until World War I. After staying neutral in the first Balkan war

(1912-1913) Romania joined Greece, Serbia, Montenegro and Turkey

against Bulgaria in the second Balkan war. The peace treaty of Bucharest

(1913) marked the end of that conflict and under its provisions

Southern Dobrudja - the Quadrilateral (the Durostor and Caliacra

counties) became part of Romania.

|

Ion I.C. Bratianu, Prime Minister of Romania

|

In August 1914, when

World War I broke out, Romania declared neutrality. Two years

later on August 14/27, 1916 it joined the Allies, which promised

support for the accomplishment of national unity; the government

led by Ion I.C. Bratianu declared war on Austria-Hungary. |

After the first success, the Romanian

army was forced to abandon part of the country, Bucharest included

and to withdraw to Moldavia, owing to the joint offensive of the

armies in Transylvania, commanded by General von Falkenhayn and

those of Bulgaria, commanded by Marshal von Mackensen.

| In the summer of

1917, in the great battles of Marasti, Marasesti and Oituz,

the Romanians aborted the attempt made by the Central Powers

to defeat and get Romania out of the war by occupying the rest

of her territory. |

Fighting at Marasesti

- Engraving of WWI

|

But the situation changed completely

following the outbreak of the revolution in Russia (1917) and the

separate peace concluded by the Soviets at Brest-Litovsk (March

3, 1918); this triggered the end of the military operations on the

eastern front. Romania was compelled to follow in the steps of her

Russian ally, because on the Moldavian front the Romanian troops

were interspersed with the Russian ones and it was impossible for

combat to continue on one area of the front and for peace to settle

on another front area, and so on. Cut off from its western allies,

Romania was forced to sign the peace treaty of Bucharest with the

Central Powers (April 24/May 7, 1918). The ratification procedure

was never carried through, so from the legal standpoint the treaty

was never operative; in fact, in late October 1918, Romania denounced

the treaty and re-entered the war.

|

Romanian army crossed

the Carpathians

to free Transylvania, an ancient Romanian land

|

The right of the

peoples to self-rule triumphed in the final stage of World War

I and this served the cause of the Romanians who lived in the

Czarist and Austro-Hungarian Empires. |

The collapse of the czarist system

and the recognition by the Soviet government of the right of the

exploited peoples to self-rule allowed the Romanians in Bessarabia

to express through the vote of the national representative body

- the Country Council which convened in Chisinau - their will to

be united with Romania (March 27/April 9, 1918). The fall of the

Hapsburg monarchy in the autumn of 1918 made it possible for the

nations that had been under Austrian-Hungarian oppression to emancipate

themselves.

| On November 15/28,

1918, the National Council of Bukovina voted in Cernauti to

unite that province to Romania. |

The Metropolitan Palace of Cernauti, where

the union of Bukovina with Romania was voted (November 28,

1918)

|

|

The Great National Assembly

of Alba Iulia, on December 1 1918

|

In Transylvania the

National Assembly called at Alba Iulia on November 18/December

1, 1918 voted, within the presence of over 100,000 delegates,

to unite Transylvania and Banat with Romania. |

| So, in January 1919,

when the peace conference was inaugurated in Paris, the union

of all Romanians into one single state was an accomplished fact. |

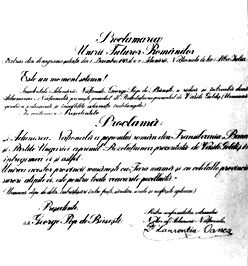

The act proclaiming the union of Transylvania to the kingdom

of Romania on December 1, 1918

|

The international peace treaties of

1919-1920 signed at Neuilly, Saint-Germain, Trianon and Paris, established

the new European realities and also sanctioned the union of the

provinces that were inhabited by Romanians into one single state

(295,042 square kilometers, with a population of 15.5 million).

The universal suffrage was introduced

(1918), a radical reform was applied (1921), a new Constitution

was adopted - one of the most democratic on the continent (1923)

- and all this created a general-democratic framework and paved

the way for a fast economic development (the industrial output doubled

between 1923 and 1938). With its 7.2 million metric tons of produced

oil in 1937, Romania was the second largest European producer and

number seven in the world. The per capita national income reached

$94 in 1938 as compared to Greece - $76, Portugal - $81, Czechoslovakia

- $141, and France - $246.

| In politics many

parties competed with one another, so the government was controlled

over the years by several of them: the Peoples Party (Alexandru

Averescu), the National Liberal Party (Ion I.C. Bratianu,

I.G. Duca, Gheorghe Tatarescu) and the National Peasant

Party (Iuliu Maniu). |

Iuliu Maniu,

President of the National Peasant Party

|

The Romanian Communist Party, established

in 1921, and which had an insignificant number of members, was banned

in 1924. The Iron Guard, an extremist right-wing nationalist movement,

established by Corneliu Zelea Codreanu in 1927, was equally

banned. In 1930 Carol II changed his mind about his earlier

decision to give up the throne, he dethroned his minor son,

Michael (who had become king in 1927) and he took the throne.

Eight years later he established his personal dictatorship (1938-1940).

|

Nicolae Titulescu, Romanian

Foreign Minister,

supporter of collective security in Europe

|

The goals of the foreign policy

in the inter-war period, when Nicolae Titulescu played

a major role, sought to maintain the territorial status quo

by creating regional alliances, supporting the League of Nations

and the collective security policy, as well as by promoting

close co-operation with the Western democracies - France and

Great Britain.

|

With Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia,

Romania lay the foundation in 1920-1921 for the Little Entente and

in 1934 Romania created with Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey a new

organization of regional security - the Balkan Entente.

Nazi Germany was rising and, together

with Italy it supported the revisionist states neighboring Romania;

the force policy was successful on the continent and this was marked

by the Anschluss, the Munich Pact (1938), the break-up of Czechoslovakia

(1939); there was rapprochement between the Soviet Union and the

Third Reich; all this led to Romanias international isolation.

The von Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact (August 23, 1939) stipulated in

a secret protocol the Soviet "interest" in the Baltic states, eastern

Poland and the Soviet similar "interest" in Bessarabia.

When World War II broke out, Romania

declared neutrality (September 6,1939) but she supported Poland

(by facilitating the transit of the National Bank treasure and granting

asylum to the Polish president and government). The defeats

suffered by France and Great Britain in 1940 created a dramatic

situation for Romania.

|

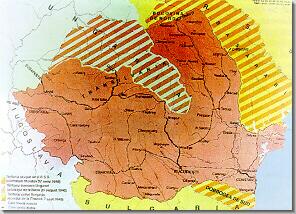

The Soviet government applied

Plank 3 of the secret protocol of August 23, 1939 and forced

Romania by the ultimatum notes of June 26 and 28, 1940 to

cede not only Bessarabia, but also Northern Bukovina and the

Hertza land (the latter two had never belonged to Russia).

Under the Vienna "Award" - actually a dictate - (August 30,

1940) Germany and Italy gave to Hungary the north-eastern

part of Transylvania, where the majority population was Romanian.

Following the Romanian-Bulgarian talks in Craiova, a treaty

was signed on September 7, 1940, under which the south of

Dobrudja (the Quadrilateral) went to Bulgaria.

|

Romania's map with the

territorial losses of the '40s

|

The serious crisis in the summer of

1940 led to the abdication of King Carol II in favour of his son

Michael I (September 6, 1940); equally, it led to General Ion Antonescus

take-over of the government (he became a Marshal in October 1941).

In an effort to win support from Germany and Italy, Ion Antonescu

joined forces in government with the Iron Guard Movement. The Movement

attempted by way of the rebellion of January 21-23, 1941 to take

over the entire government and, as a result, it was eliminated from

politics.

|

June 22, 1941: the Romanian

army crosses the river Prut

to liberate Bessarabia occupied by the Soviets

|

Wishing to get back the territories

lost in 1940, Ion Antonescu participated, side by side with

Germany, in the war against the Soviet Union (1941-1944).

|

The defeats suffered by the Axis powers

led after 1942 to enhanced attempts made by Antonescus regime,

as well as by the democratic opposition (Iuliu Maniu, C.I.C.

Bratianu) to take Romania out of the alliance with Germany.

On August 23, 1944, Marshal Ion Antonescu was arrested under the

order of King Michael I.

| The new government,

made up of military men and technocrats, declared war on Germany

(August 24, 1944) and so, Romania brought her whole economic

and military potential into the alliance of the United Nations,

until the end of World War II in Europe. |

Romanian machine gunners in action

in the mountains of Czechoslovakia

|

|

Despite the human

and economic efforts Romania had made for the cause of the

United Nations for nine months, the Peace Treaty of Paris

(February 10, 1947) denied Romania the co-belligerent status

and forced her to pay huge war reparation. payments; but the

Treaty recognized the come-back of north-eastern Transylvania

to Romania while Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina stayed annexed

to the USSR.

|

The Romanian army was triumphal received

in all the localities of Transylvania

|

On the territory of Romania Soviet

troops were stationed and the country was abandoned by the Western

powers, so the next stage brought a similar evolution to that of

the other satellites of the Soviet Empire. The whole government

was forcibly taken over by the communists, the political parties

were banned and their members were persecuted and arrested; King

Michael I was forced to abdicate and the same day the peoples republic

was proclaimed (December 30, 1947).

|

The single-party dictatorship

was established, based on an omnipotent and omnipresent surveillance

and repression force.

The industrial enterprises,

the banks and the transportation means were nationalized (1948),

agriculture was forcibly collectivized (1949-1962), the whole

economy was developed according to five-year plans, the main

goal being a Stalinist type industrialization. Romania became

a founding member of COMECON (1949) and of the Warsaw Treaty

(1955).

|

The communists took charge of the state,

guided by their utopian, noxious creed

|

At the death of Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej

(1965), the communist leader of the after-war epoch, the party leadership,

which was later identified with that of the state as well, was monopolized

by Nicolae Ceausescu. In a short period of time he managed

to concentrate into his own hands (and those of a clan headed by

his wife, Elena Ceausescu) all the power levers of the communist

party and of the state system. Romania distanced herself from the

USSR (this publicy inaugurated in the "Statement" of April 1964);

the domestic policy was less rigid and there was some opening in

the foreign policy (Romania was the only Warsaw Treaty member-state

that did not intervene in Czechoslovakia in 1968); all this, as

well as the political capital built on such a less Orthodox line

were used to consolidate Ceausescus own position, to take over

the whole power within the party and the state. The dictatorship

of the Ceausescu family, one of the most absurd forms of totalitarian

government in the 20th century Europe, with a personality cult that

actually bordered on mental illness, had as a result, among other

things, distortions in the economy, the degradation of the social

and moral life, the countrys isolation from the international community.

The countrys resources were abusively used to build absurdly giant

projects devised by the dictators megalomania; this also contributed

to a dramatic decline of the populations living standard and the

deepening of the regimes crisis.

|

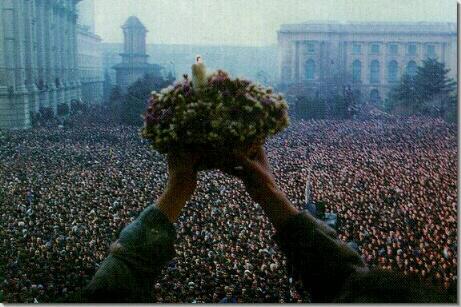

The Romanian Revolution of December 22, 1989

|

Under these circumstances,

the spark of the revolt that was stirred in Timisoara on December

16, 1989 rapidly spread all over the country and in December

22 the dictatorship was overthrown owing to the sacrifice of

over one thousand lives. |

The victory of the revolution opened

the way for a re-establishment of democracy, of the pluralist political

system, for the return to a market economy and the re-integration

of the country in the European economic, political and cultural

space.

|